Film Analysis: Hereditary (2018)

Ari Aster's 'Hereditary' as a meditation on familial trauma, mental health and representations of motherhood.

Hereditary 2018, dir. Ari Aster. Cast: Milly Shapiro, Toni Collette, Gabriel Byrne, Alex Wolff. (Photo courtesy A24/Reid Chavis)

When looking at the idea of trauma and loss, the ideal film which comes to mind, when discussing these themes, is the newest release from the production company A24, Hereditary. Hereditary is film which essentially tells the story of a family falling apart whilst dealing with the impact of a traumatic event in which every member within the family dynamic has a place. Hereditary deals with loss and trauma and expansively translates that into the idea of a horror fuelled narrative with an effectiveness that has perhaps not been seen in mainstream horror movies since the likes of The Exorcist. Where the frequently expressed perception of Hereditary being somewhat similar to The Exorcist is not just due to the reaction which it has gained from audiences wherever it has been released, but is due to the themes it deals with, as will be explored later. The concept of loss should be introduced here without further hesitation, if only to highlight that loss is only relative, for example with respect to those that have actually lost the thing which did (or rather had) gone before. For example, if a loved one dies the loss of life is not of course 'felt' by the unfortunate individual who actually lost their life, the entire extent of the loss is felt by those who surrounded / were closely familiar with the one who passed away, but who remained living. In this respect it could be said that deceased person had not 'lost' their life per se, but the loss of their presence was very much felt by those remaining alive who loved or cared about them. Within Hereditary the world that the family inhabits is dominated by memory. The very title itself has parallels that are redolent not just of physical heredity, but also of a form of 'genetic' memory too. One definition of hereditary is “(of a characteristic or disease) determined by genetic factors and therefore able to be passed on from parents to their offspring or descendants.” The sense behind this definition inhabits the very fibre of Hereditary. The family portrayed in the film ultimately have to deal with issues that had already pervaded older generations and it is the 'sins' of the older generation which ultimately come back to haunt them too. Hereditary is in essence a film dominated at its core by a form of collective, cross generational familial memory. Its central characters are infatuated with the memory of lost family members and it is this memory which returns to haunt the family rather than merely the supernatural entities themselves that, from a narrative perspective, the film could be said to be following.

Hereditary opens with an inter-title referencing an obituary to be printed in a local newspaper describing the death of Ellen Leigh, the mother of the protagonist Ellie. From the outset, the director, Ari Aster, instills the ideas of loss and grief as a theme of the film. The first notable live action shot is that of models in the house. The reason this shot is so significant is that it begins where the film ends, the tree house. With a slow pan around the room we see various models of houses before dollying in to the model of the house in which the film is set. Through Aster deciding to use this movement with the camera it subconsciously plants the idea within the audience that what we are about to witness is not in fact what is truly happening, and that the film is simply a representation of the inner mind of an individual traumatised by the loss of her family, or perhaps also grieving over that family dynamic falling apart. Where this eventually becomes truly apparent is only in the very last shot of the entire film where the satanic cult that has been attempting to put Charlie, the daughter, into the body of the son, Peter, because they believe her to be a physical representation of King Paimon, a deity who resides in hell, finally achieve their goal in the tree house of the Graham family home. During the final moments of this scene the camera almost pops backwards to create the impression that the tree house is in fact the model in the room we saw at the beginning of the film.

Milly Shapiro in Hereditary. (Photo courtesy A24/Reid Chavis)

Hereditary. (Photo courtesy A24/Reid Chavis)

The following scenes follow the central family at the funeral of the matriarch, Ellen. The protagonist, Annie, describes in a eulogy her mother’s life and that she was a private person with private ‘rituals.’ Ultimately the eulogy can be directly linked to the last ten minutes of the film, however at this stage it serves as a convincing representation of the sense of ordinary grief over a family member who has recently passed away. This perception of grief is thematically pursued throughout, in parallel with issues relating to alcoholism. The connection is made when Annie goes to a counselling meeting in which people dealing with grief come together and talk about the issues they have been facing, similar to that of an alcoholics anonymous meeting. Where the notions of grief and addiction start to collide is when Annie starts to describe her traumatic family history, in particular their struggles with mental illness which both her mother, father, and brother, had to either live with or end their own lives to deal with. It might be considered strange to say someone is addicted to grief but when looking at the protagonist of Hereditary it is easy to see that Annie very much lives for, and perhaps enjoys, being in a constant state of grieving or emotional turmoil. The evidence for this comes just before a dinner scene that results in a semi-permanent rupture between remaining family members. Annie is working in her workshop and is making an extremely detailed model of the accident which had just recently killed her daughter, Charlie. While Annie explains to her husband that the model is purely ‘a neutral view of the accident’ it is clear to see that she is in reality addicted to grieving, she is unable to let trauma go and instead holds onto it as well as recreating it in extremely graphic detail.

Aside from its examination of the effects of grief and trauma on the human psyche, Hereditary, also deals with issues of representation. From the film's marketing material, it is highlighted that the main ‘antagonist’ is the daughter, Charlie. It is not, however, clear that the character of Charlie and the ordeal she goes through, namely dying violently and then having her soul 'placed' in her brother’s body, is necessarily a representation of femininity within modern society. The world is becoming more and more globalised as time moves on. Newer technology means that we, as a species, can cross the globe in less than a day, call somebody who is thousands of miles away and hear their voices, send a message around the world which reaches its destination in less than a second. By many measures the human race is at its most 'advanced' point in recorded history. When it comes to the very fundamental question of biology, however, humans, as a species, remain remarkably primal and animalistic. As a global society there is still wide discrimination between males and females, with females being paid much less and not being treated with the amount of respect they deserve. Hereditary analyses this perfectly, yet such reflections relating to political principles are told through the use of a supernatural being, that of King Paimon. Towards the end of the film, Annie finds a passage in one of her mother’s books where we learn who and what Paimon is. The passage reads ‘Paimon is a male entity and thus is covetous of a male body.’ Once Charlie inhabits Peter’s body, she is then acceptable to both the cult as well as the demon itself. This, it could be argued, is simply a comment from the filmmaker on the nature of biological differences that still pervade modern society and influence political and economic policies within governments and private companies. Through having this be the central point upon which the film revolves Aster is commenting that in the modern world for a woman to be taken seriously she has to act as a man would, otherwise she would not be desirable either in personal or work relationships. The exploration of gender is not something which many mainstream films, let alone horror films, are always discussing and the nature with which Hereditary deals with this representation of gender serves as an excellent piece of political commentary.

The first act of Hereditary is where Ari Aster fully utilises memory as a way of translating grief through the characters. Within the first ten minutes of the opening credits the protagonist has already spoken about her mother twice, once at the funeral and another when she is putting her daughter to bed. From both of these interactions we are able to see how the memory of her mother is still playing on her mind and potentially perpetuating trauma. For example when Annie is putting Charlie to sleep we learn that Leigh, Annie’s mother, would not allow Annie herself to breastfeed Charlie and while at that moment there is no overt hint of trauma from the character of Annie, it is when she is alone in her workshop that traumatic memories resurface. Once Annie goes into her workshop she looks through books about spiritualism which belonged to Leigh. As she is leaving the room she turns the light off and we see a figure standing in the corner of the room, smiling and staring at Annie. Annie switches the light back on and the figure disappears. Scanning the room Annie locks eyes on a model and then goes to turn it around to the camera where the audience sees a model representation of the exact scene that Annie had just been describing. This is where the idea of trauma becomes apparent within the character of Annie, but also illustrates how she might also be addicted to it. This is because Annie constantly reminds herself of the traumatic events which she has dealt with in the past and uses her memories of them to 'recreate' them afresh.

Hereditary (2018). Photo courtesy A24/Reid Chavis.

Milly Shapiro, Toni Collette in Hereditary.

In the next few scenes Annie attends group counselling sessions dealing with issues like grief. It is here that we learn about the events that have pervaded her family history. Through hearing about the struggles with mental health both her father, mother, and brother had to deal with we see the nature of the subjectivity of human memory. Memory in its very nature is subjective to the one remembering and two people may remember the same event very differently. Throughout this scene we see this subjectivity in action where Annie puts her mother in the centre of all the problems and traumas that the family faced. For example she talks about her brother killing himself and then proceeds to describe in detail the suicide note that was left, which contained passages that blamed Leigh for putting people inside of him. Annie opens up in the group meeting about this because of how it reflected on the relationship that she had with her mother. Throughout this entire scene, Annie never once tries to make excuses for the actions of her mother and does not even disavow the idea that was contained in the suicide note.

The critical juncture of the first act is ultimately what represents the entirety of the second act, Charlie’s death. After going to a party with her brother, Peter, Charlie accidentally eats nuts and she starts to have an allergic reaction. As they’re driving home Peter starts to exceed the speed limit in response to Charlie sticking her head out of the window, trying to breath. But then out of the blue, Peter had to swerve to avoid a dead deer in the road which resulted in Charlie being decapitated by a lamp post. The remainder of the second act focuses on the remaining family members dealing with the loss of Charlie. When reiteration of memory comes to the fore, it serves to give rise to repetitive cycles of grief and trauma, especially in the case of Peter. Subsequently a dinner table scene occurs where Annie and Peter have a violent argument where they both try and blame each other for the death of Charlie. If Peter had stayed with Charlie she would not have had a reaction to nuts, however Charlie would not have been at the party to begin with had she not been forced to go by Annie. Once again this is where the subjectivity of memory comes into play, Annie believes that Peter is to blame whilst Peter is equally convinced that Annie is to blame. While Peter clearly feels guilty for being the one who directly contributed to the death of his sister, he remembers the entire scenario through an entirely different prism to Annie. There are a couple of examples that can be highlighted here. The first is that Annie is ultimately consumed by the details of the accident itself, not the events surrounding it which is revealed when she describes to her ‘friend’ Joan the details of the description of the scene when she found Charlie’s body. The second is that Annie makes a highly graphic model of the accident and puts painstaking amounts of detail into it. This is where Ari Aster emphasises the memory of trauma that Annie cannot let go of. As mentioned previously, Peter is traumatised on a much broader scale as he chooses to remember not just the event of Charlie’s death but all the events leading up to it. The subjectivity, from Peter’s perspective, comes when he is looking for someone to pin the blame on. From Peter’s point of view he is not at fault, because if it was not due to Annie’s interference beforehand then Charlie would not have been in the car.

The third act of Hereditary is where memory starts to physically tear the family apart as well as the individual psyche of each member of the family dynamic. With Annie, she starts to dive into the world of the occult and becomes obsessed with being able to communicate with Charlie in the afterlife. Through this she succeeds in bringing Charlie back as a vengeful spirit rather than the quiet, weird girl that she was when she was alive. It is almost as if the memory of her experience changed the way in which she perceived her family and that this memory caused her to wreak revenge on them for putting her in the situation in which she found herself. This is where the idea of loss that was mentioned earlier comes to the fore. At the time of Charlie’s death she was not aware of the loss of her life, but upon being conjured back to the physical realm she then became aware of what she had lost and her 'recovered' memory of that ultimately changed her (spirit) personality. Where the memory of the events of the second act affect Peter is when he slowly starts to lose his grip on reality. At points during the finale he is literally slapping himself, trying to wake himself up. The loss of functional mental health starts to affect his physical health too as he smashes his head into his own desk. On a surface narrative level, Peter is being possessed by Charlie when he does this act, however looked at from another way, it could be said to be Peter was literally trying to beat the memory of the death of his sister from his mind.

Alex Wolff in Hereditary. Photo courtesy A24/Reid Chavis.

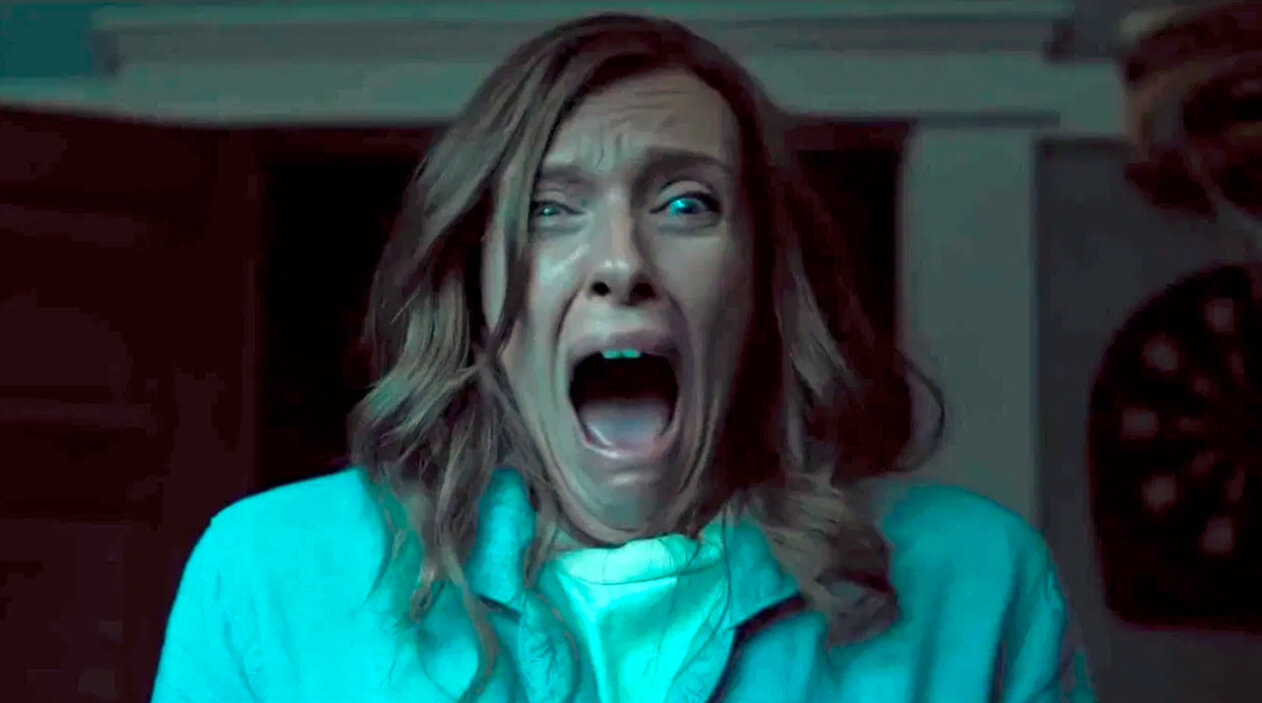

Toni Collette in Hereditary. Photo courtesy A24/Reid Chavis.

The aesthetic choices that Ari Aster chooses to use arguably carry as much weight in translating the theme of grief (i.e. loss and trauma) as the narrative choices do. The reality with Hereditary is that Aster uses aesthetic elements to create the initial theme of grief and then expands on that to simulate the inner emotions that each of the characters are feeling. There are several key examples such as the use of dull colour to the transitions from day to night which all work coherently together to exaggerate the grief that is felt by the central characters.

The most notable of the aesthetic decisions made by the director are the scene transitions. There are two points in the film where unique transitions are used between scenes that works to accentuate the perception of grief and trauma. What could be regarded as the singular best use of scene transitions would be regarding Peter as he moves between time and location without physically moving at all. This takes place soon after Charlie has been killed and Peter is sat on the edge of his bed, contemplating. After a second the scene switches; Peter has not moved, yet he is now sat in a classroom in the middle of the day. The reason that this is raised is because of the way it represents the emotional turmoil that is unfolding within the character of Peter. Through using this type of scene transition, the director has perfectly encapsulated the feeling of loss, trauma, and grief. When a person is grieving or is in a depressed state of mind, research suggests that time becomes relative to that person. A filmic example of this would be Melancholia by Lars von Trier where the main character suffers from depressive episodes which means the world around her moves slower and she finds herself in strange places. Through using the scene transitions that Aster uses it creates the same effect that von Trier did in Melancholia; the audience begins to look at events not from that of an objective outside looking at scenes unfold but instead look at the scenarios that the characters find themselves in with full emotional engagement. Aster has transported the audience into the mind of someone who is grieving and suffering from the trauma of the loss of a close family member. Within Hereditary the only other time that these unique scene transitions are used is an exterior shot looking at the house and the night switches to day. The effect of this is that it widens the scope of the feeling of depression. Instead of simply looking at one character we, as the audience, look at the entire house as the time starts to almost warp around them which inherently suggests that the loss and trauma felt by Peter is not singular, the entire family is experiencing something similar. To illustrate the complexity of this close relation between the natural and supernatural worlds, at a point in the narrative where physical time becomes temporal, due to Peter’s lack of emotional engagement triggered by the trauma he experienced, Burgoyne makes a strong point that ‘Perhaps the greatest champion of the realist vocation of the cinema, Bazin argued that the realism of cinema derived from its existential relation to the physical world: the same rays of light that fell … are there to be imprinted on the photographic emulsion which preserved that very same light like a fly preserved in amber’.

Toni Collette in Hereditary. Photo courtesy A24/Reid Chavis.

Hereditary (2018) Photo courtesy A24

Hereditary (2018) Photo courtesy A24

The other notable aesthetic choice that is made within Hereditary is the colour scheme. As was mentioned earlier, the film starts with an intertitle in the form of an obituary which means, from the very outset of the film, the tone of grief is set and this means that the colour scheme reflects that. Throughout the film there is little to no use of bright colours and instead the director opts to use a very muted colour scheme. The effect of this is very similar to that of the scene transitions where it simulates the feelings of grief, trauma and loss. While a person who suffers with depression also loses track of time, there’s a significant loss in the perception of the world around them. Things that made somebody happy or brought joy into their lives lose that ability to evoke the same feeling. In filmic language this is a considerably difficult feeling to put across to the audience, but it is also extremely difficult to bring the audience into that world. The most effective way to do this is through the colour grading where colours can be muted and contrast lowered. This is exactly what Aster chooses to do. Through having the muted, and almost drab, colours the director pulls the audience into the inner emotions of the characters and does an exemplary job of representing what it is like for a person who’s having to deal with grief and depression. Once again, as soon as Charlie has been killed the colours take on a decidedly darker tone and this shows how the entire family are trying to deal with the loss of the youngest member of the family unit. According to Darian Leader, a practising psychoanalyst in London and a member of the Centre for Freudian Analysis and Research; he pre-supposes the ‘whether or not we are able to mourn’, despite having fallen into a nightmare of depression, lose the will to live and see no hope for the future. This is exemplified in an earlier shot in the film, Annie is seen struggling to brace herself on her bedroom floor, clawing it in denial at the discovery of her daughter’s headless body in the car outside.

To conclude, the film Hereditary is one that is infused, perhaps even infatuated with memory; it is the cornerstone of the entire piece. Memory dominates every facet of the psyche of the main characters and influences the film’s plot to a substantial degree. From a narrative perspective, Aster deals with themes and ideas that are subsidiary to the central theme of memory and grief; even those of a political nature. The main aspect of the film that one should be reminded of is the representation of women due to it being a piece of excellent social commentary on the state of gender in the modern world. Through placing the central protagonist, Annie, is a state of perpetual grief and depression, Aster is able to properly examine what it means to be depressed, in that a memory continues to haunt and eventually it will devour someone if it is given the power to do so. Through showing Annie recreating models from her own memory the director has been able to show how the memory of certain events have devoured Annie and work only to keep her in the same state of perpetual grief, a milieu that the film also firmly inhabits.

Written by Louis Holder.

Bibliography Available with Citations & References.

This horror film you can watch on Netflix.